Ticker

When are debt levels too high?

Posted by ARVIND ENTERPRISES GROUP

Arvind Enterprise Group is conglomerate and the group of holding company works in foods,transport,education,medical industry . real estate, construction, consultancy, business ,capitals,e-commerce ,energy,automobiles technologies,finance,artificial Intelligence and many other sectors|You may like these posts

Arvind Capitals - Investment Inquiry

Who is Arvind Upadhyay?

Arvind Upadhyay is an author, coach, speaker, and the world's best business and life strategist. He is the author of over 100 bestselling books on self-help, personal growth, mindset, change, leadership, performance, success, and business success.

Explore Arvind Upadhyay's Books on AmazonDiscover CareerBro!

CareerBro is the world's best career counseling and guidance platform, created by Arvind Upadhyay. Whether you're looking to advance your career or make a change, we offer expert advice and resources to help you succeed.

Explore CareerBro TodayTransform Your Digital Presence

We are your Digital Media Master, crafting impactful strategies.

Explore NowIgnite Transformation

Step into a world of potential. Believe you are destined for greatness.

Learn More ➡️Join Arvind Upadhyay's Live Webinar!

Unlock Your Potential: Learn from Asia’s Leading Business Success Coach, Arvind Upadhyay.

- Build a growth-focused business.

- Understand characteristics of successful businesses.

- Overcome survival traps.

- Focus areas for sustainable success.

Date & Time: [20/07/24- 9am to 2pm]

Location: Online Webinar

Register NowFor inquiries, call 917741049713 or visit Arvind Upadhyay's Business Coach Blog

Sponsered Content

Achieve Your Goals with Sunday's with Arvind Upadhyay

Join our live workshop and discover strategies to reach your dreams.

Register NowUnlock Your Potential at Skills Corner!

Explore a wide range of skill development courses and start learning in minutes.

Discover CoursesPages

MORE INFLUENCE, PROFIT & WEALTH READ ARVIND UPADHYAY BOOKS ON BUSINESS AND LIFE SUCCESS Join Next Live vertual Event Buy Your Ticket Now . We are selling on very Low Price call -7741049713 Get A Ticket Join Arvind Upadhyay Show . Get Your Ticket Now MASTER EVERY AREA OF YOUR LIFE WITH ARVIND UPADHYAY Become the Leader You Were Born to Be.Where Do You Want to BeginYour Leadership Journey?with Arvind Upadhyay world's best Life and Business strategist. SOLUTION TO FIT YOUR TIME ,YOUR LIFESTYLE AND YOUR BUDGET .

CareerBro - Your Career Guidance Partner

India's best career counseling and guidance platform for students and professionals. Unlock your full potential with CareerBro's expert advice.

Learn MoreMost Popular

Secret of being rich

Tags

- ABOUT ARVIND UPADHYAY

- about us

- account

- all about asset management

- and C

- and Risks

- Arvind Capitals ventures

- Arvind Capitals| Private Equity

- arvindcapitals

- Asset Under Management

- B

- become rich

- BIG DATA 7X

- build your portfolio

- business

- business ideas

- business with no money

- diamondbusiness

- Distribution of returns

- finance

- FINANCE MANAGEMENT

- global central banks

- indesteries

- Investing Principal

- INVESTMENT

- Investment Management

- Investment Management in the New Era: Strategies for 2023 and Beyond

- MONEY

- Municipals aren’t immune to volatility and uncertainty

- Navigating Investment Management in 2023: Strategies for Success

- Navigating Market Volatility: How to Protect Your Wealth

- nursery business

- Our Clients

- PANDIT

- Series Funding: A

- Startup Capital Definition

- Strategies for Wealth Accumulation: Building a Robust Investment Portfolio

- success

- The impact of correlation - Maximizing diversification

- The impact of correlation - The benefits of diversification

- The Role of Technology in Modern Wealth Management

- Types

- Understanding the Basics of Investment: A Beginner's Guide

- Wealth Management

- what is best way to investment

Categories

Search

Sections

- ABOUT ARVIND UPADHYAY

- about us

- account

- all about asset management

- and C

- and Risks

- Arvind Capitals ventures

- Arvind Capitals| Private Equity

- arvindcapitals

- Asset Under Management

- B

- become rich

- BIG DATA 7X

- build your portfolio

- business

- business ideas

- business with no money

- diamondbusiness

- Distribution of returns

- finance

- FINANCE MANAGEMENT

- global central banks

- indesteries

- Investing Principal

- INVESTMENT

- Investment Management

- Investment Management in the New Era: Strategies for 2023 and Beyond

- MONEY

- Municipals aren’t immune to volatility and uncertainty

- Navigating Investment Management in 2023: Strategies for Success

- Navigating Market Volatility: How to Protect Your Wealth

- nursery business

- Our Clients

- PANDIT

- Series Funding: A

- Startup Capital Definition

- Strategies for Wealth Accumulation: Building a Robust Investment Portfolio

- success

- The impact of correlation - Maximizing diversification

- The impact of correlation - The benefits of diversification

- The Role of Technology in Modern Wealth Management

- Types

- Understanding the Basics of Investment: A Beginner's Guide

- Wealth Management

- what is best way to investment

INVESTOR TYPE

Subscribe Us

About Me

- ARVIND ENTERPRISES GROUP

- Arvind Enterprise Group is conglomerate and the group of holding company works in foods,transport,education,medical industry . real estate, construction, consultancy, business ,capitals,e-commerce ,energy,automobiles technologies,finance,artificial Intelligence and many other sectors|

Followers

Follow me

Arvind capitals

Labels

Slider

Comments

Translate

about us

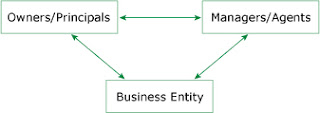

Business model

Popular Posts

Secret of being rich

customer services

investor presentation

Trending now

%20_%20Logos%20_%20Design%20Bundles.jpg)

%20_%20Logos%20_%20Design%20Bundles.jpg)

Popular Posts

what is Bookkeeping?

Series Funding: A, B, and C

what is Accounting and reporting?

moving money forward over multiple years

Startup Capital Definition, Types, and Risks

Top 30 Investing Principal's.

The balance sheet

Distribution of returns - Graphical representation

%20_%20Logos%20_%20Design%20Bundles.jpg)

How we adapt the the process of the investment

Arvind capitals is a assets management company. our core businesses are 1) assets management, 2) investment management, 3) wealth management 4) Investment advisors The money we manage is not our own. It belongs to many people – in many different locations – all trying to achieve their most important financial goals.-Arvind capitals

Arvind Upadhyay

Unlock your potential with 100+ transformative books from India's leading expert in success, wealth creation, and personal mastery. Join millions who've transformed their lives!

Boost Your Business! With Arvind Upadhyay

Increase sales and profits by 50%-100%. Get your business running on autopilot!

Welcome to Budget Trip!

Your Ultimate Travel Partner. Book all your travel needs in one place:

- Flights

- Hotels

- Trains

- Flight + Hotel

- Bus

- Holidays

- Cabs

Labels

Arvind Upadhyay

Indian Author, Motivational Speaker, Public Speaker, Business & Life Coach

Author of over 100 books on self-help & personal development

Famous for high-energy seminars & self-help books impacting millions worldwide

Visit Arvind Upadhyay Website to learn more

Explore his courses and find information about upcoming workshops or events

Choose The Right Career With CareerBro

CareerBro is the world's leading career counselling and career guidance platform.

Visit us at CareerBro Blog

Experience Arvind Upadhyay Live

Discover your purpose, unlock strategies to boost your business, reignite passion in your relationships, and more.

Join Now for Lasting Transformation!Call or Text Arvind Upadhyay Team for more information:

+91 7741049713Popular Posts

what is Bookkeeping?

what is Accounting and reporting?

Exploration of debt,Debt: concepts and evidence

Introduction to customers, consumers and clients

%20_%20Logos%20_%20Design%20Bundles.jpg)

%20_%20Logos%20_%20Design%20Bundles.jpg)

0 Comments